Storied Futures was first displayed in Evans Brothers Coffee Shop in May of 2023 in Sandpoint, Idaho. A condensed version will be on display at Sandpoint’s Bonner County Public Library through May of 2024.

About the Exhibit

Storied

Futures

Storied Futures is a recognition of the inherent value in learning about, preserving, and being inspired by the generations of people who built the community in which we live. It’s looking for ways to acknowledge their historic past – the stories encompassed within the traces they’ve left behind – and using what we discover to create a more thoughtful future.

From its inception, this project has been an exploration of development and preservation; about people taking opportunities and carving their mark – for better or worse – into their surroundings, and our duty to examine their (and our own) impact on our past, present, and future. Development can mean crafting something from nothing, leaving a legacy, providing for a family, and supporting a community. It can also mean growth and profit for some, at the expense and displacement of others.

These themes are familiar in our current paradigm of ever-increasing home prices and the quickly changing face of our community. By studying the successes and mistakes of the past, we can learn how to build a better future together. We invite you to explore a single Sandpoint property and see how it not only tells the stories of the families who lived within it, but the story we’re still actively writing about our community, and the legacy we, too, will leave behind.

Project Team:

Reid Weber, Architect

Hannah Combs, Historian

Emily Erickson, Writer

Cynthia Dalsing, History Enthusiast

Owen Leisy, Sandpoint High School Senior, Illustrator

This project would not have been possible without the contributions of:

Bonner County Historical Society & Museum

Dan Evans

Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson

Dixie Plata

North Root Architecture

Kit Mitchell Photography

Marianne Love

Barbara Tibbs

Laurie Tibbs

Will Valentine

Jane Fritz

Rob Hart

Nancy Hadley

Mickey & Duffy Mahoney

Kris Contor

SETTING THE STAGE

“FREE LAND” was the cry when the Homestead Act was enacted in 1862 by the Lincoln Administration.

The eastern part of the US was becoming crowded and the country embraced expansion into western lands. Of course, the land labeled “free for the taking” was occupied by millennia-old nations of Native Americans. The Act imposed western ideologies and boundaries onto people for whom land wasn’t something to own, and its stewardship was a community, rather than an individual affair.

With the increase of settlers in the west, native peoples found themselves pushed further from their homelands and sacred spaces or onto crowded reservations. The National Park Service described, “Reactions [to homesteading] were as complex and varied as the Native Americans themselves. Some looked for new opportunities. Many hoped to adapt. Others fought to hold on to their traditional ways of life. All recognized that changes would alter their lives forever.”

The Native American Tribes impacted locally by the Homestead Act were the q’lispe (Kalispel), the ktunaxa (Kootenai) and schitsu’umsh (Coeur d’Alene).

Despite its complex and controversial nature, over 60,000 US citizens would respond to the call by the Lincoln Administration for “Free land in Idaho,” eventually settling over 18% of the state. These settlers were drawn to opportunity, adventure, dreams of land ownership, and the economic potential of farming, mining, and the “untamed” west.

Many were new to the difficulties of homesteading – from the natural obstacles like severe weather conditions, lack of building materials, scarce water and heat, illness, and insects – to the lawless and lonely nature of early development, ensuring very few newcomers were prepared for or well suited to the task.

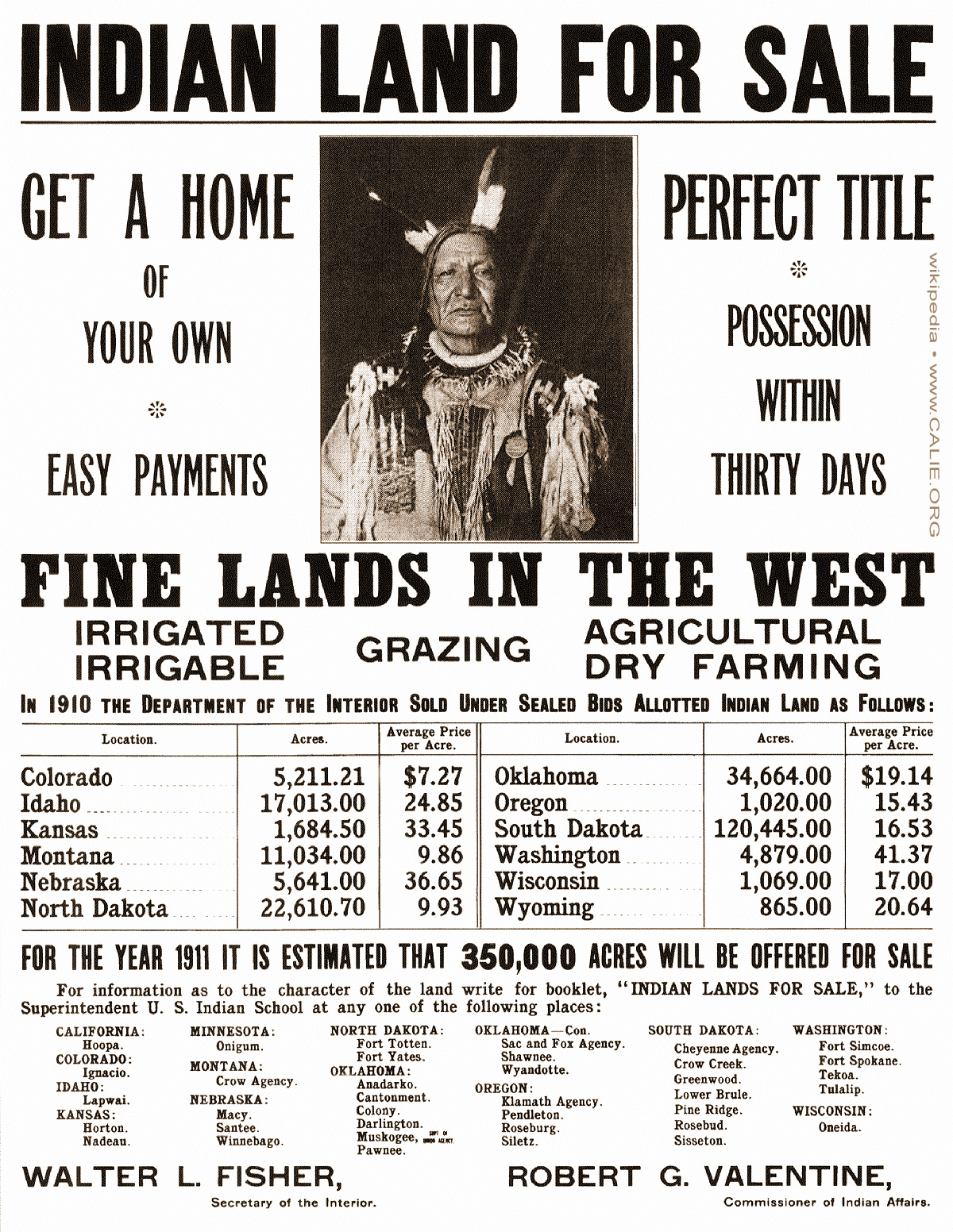

This 1911 advertisement brings into sharp relief the brutal disregard of the U.S. government for the people whose lands they were occupying and profiting from. Retrieved from the Library of Congress.

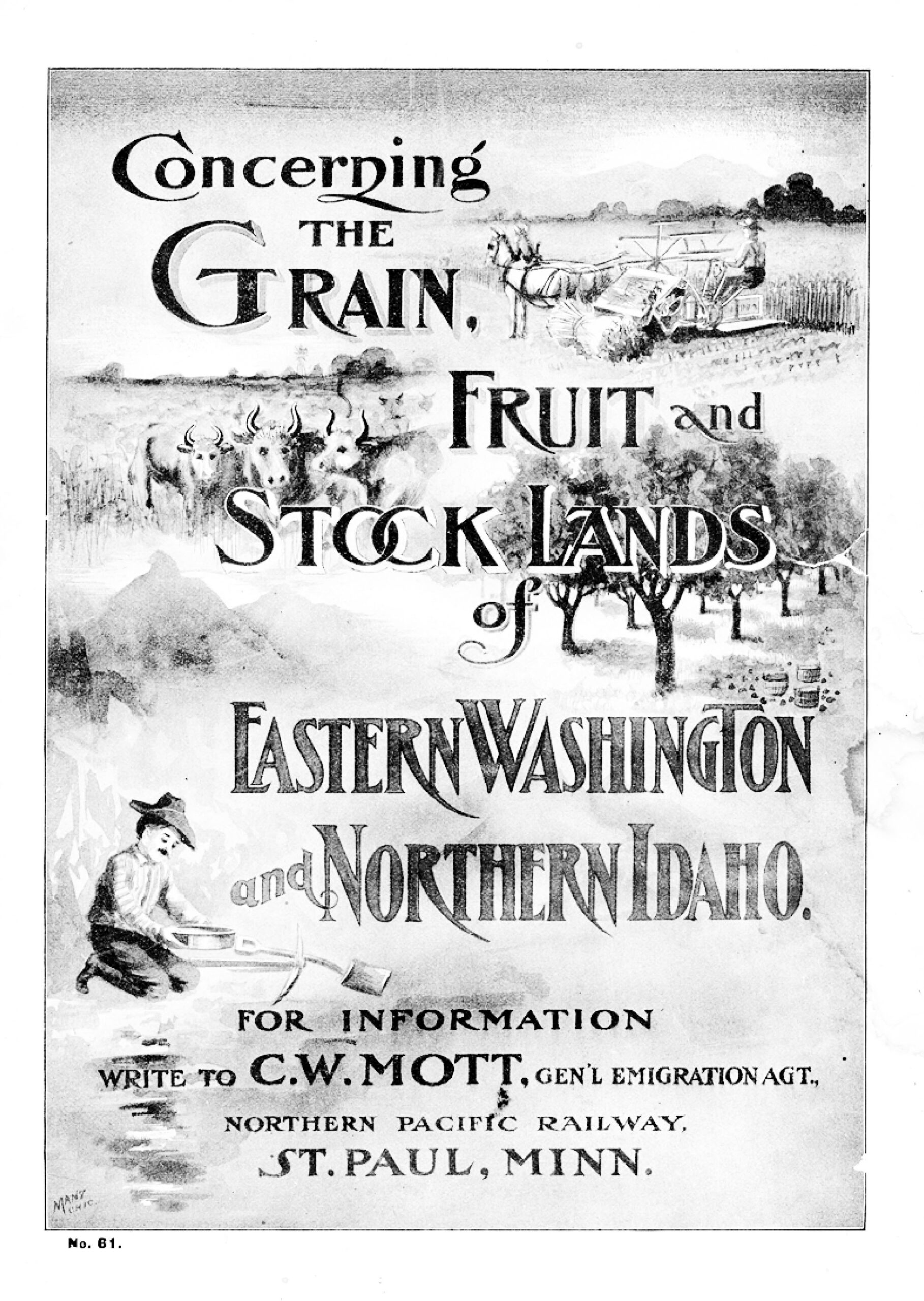

Concerning the Grain, Fruit and Stock Lands of Eastern Washington and Northern Idaho. 1902 Northern Pacific Railway pamphlet targeted to prospective pioneering farmers from the Midwest. Courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

AN OPPORTUNITY, A RISK

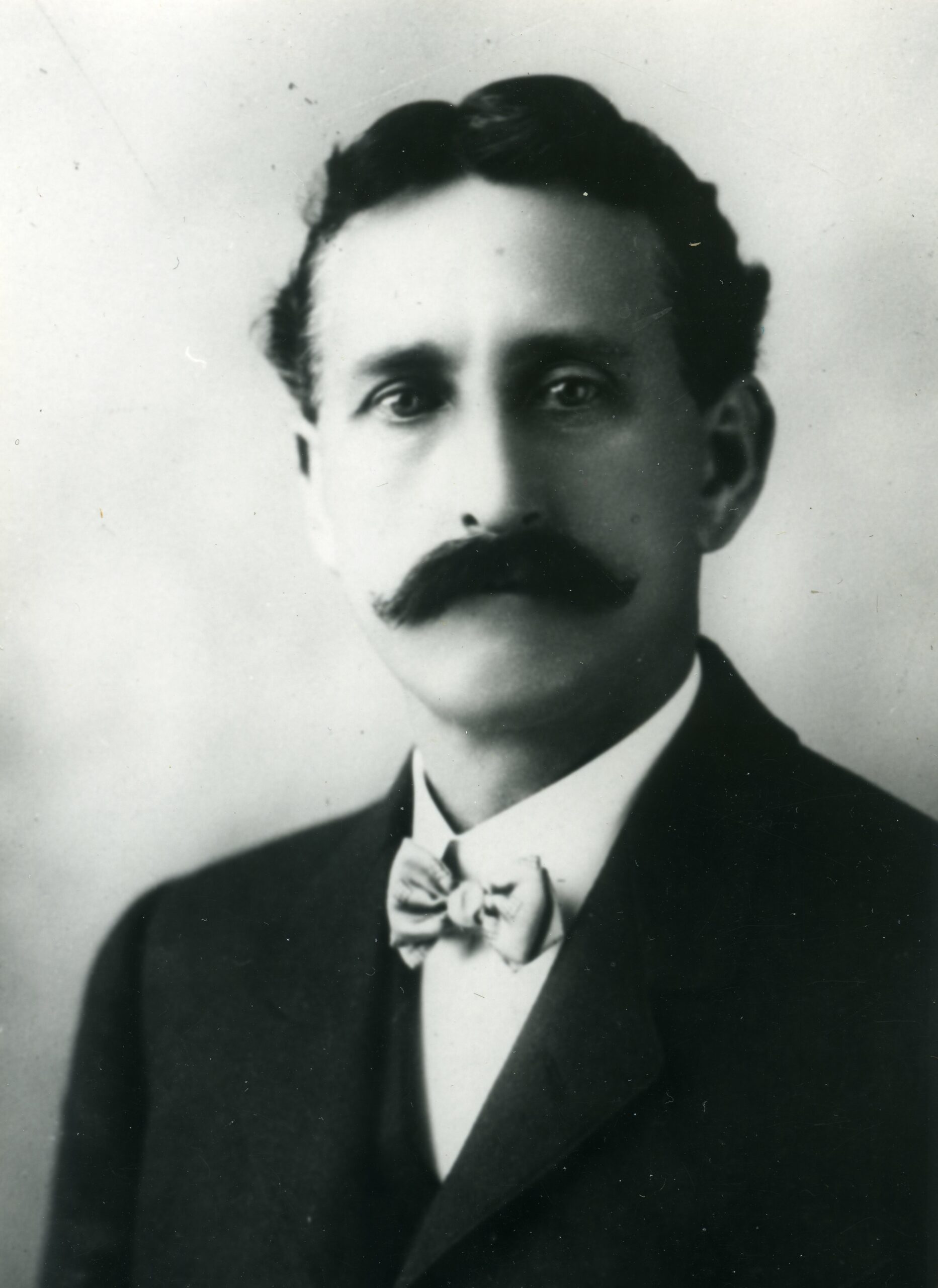

John Thomas Elsasser, born November 18, 1862, shown here circa 1884, age 22. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

William Ralph Elsasser, born March 11, 1865, circa 1884 at age 19. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

John Thomas Elsasser (Top), born November 18, 1862, shown here circa 1884, age 22. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

William Ralph Elsasser (Bottom), born March 11, 1865, circa 1884 at age 19. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

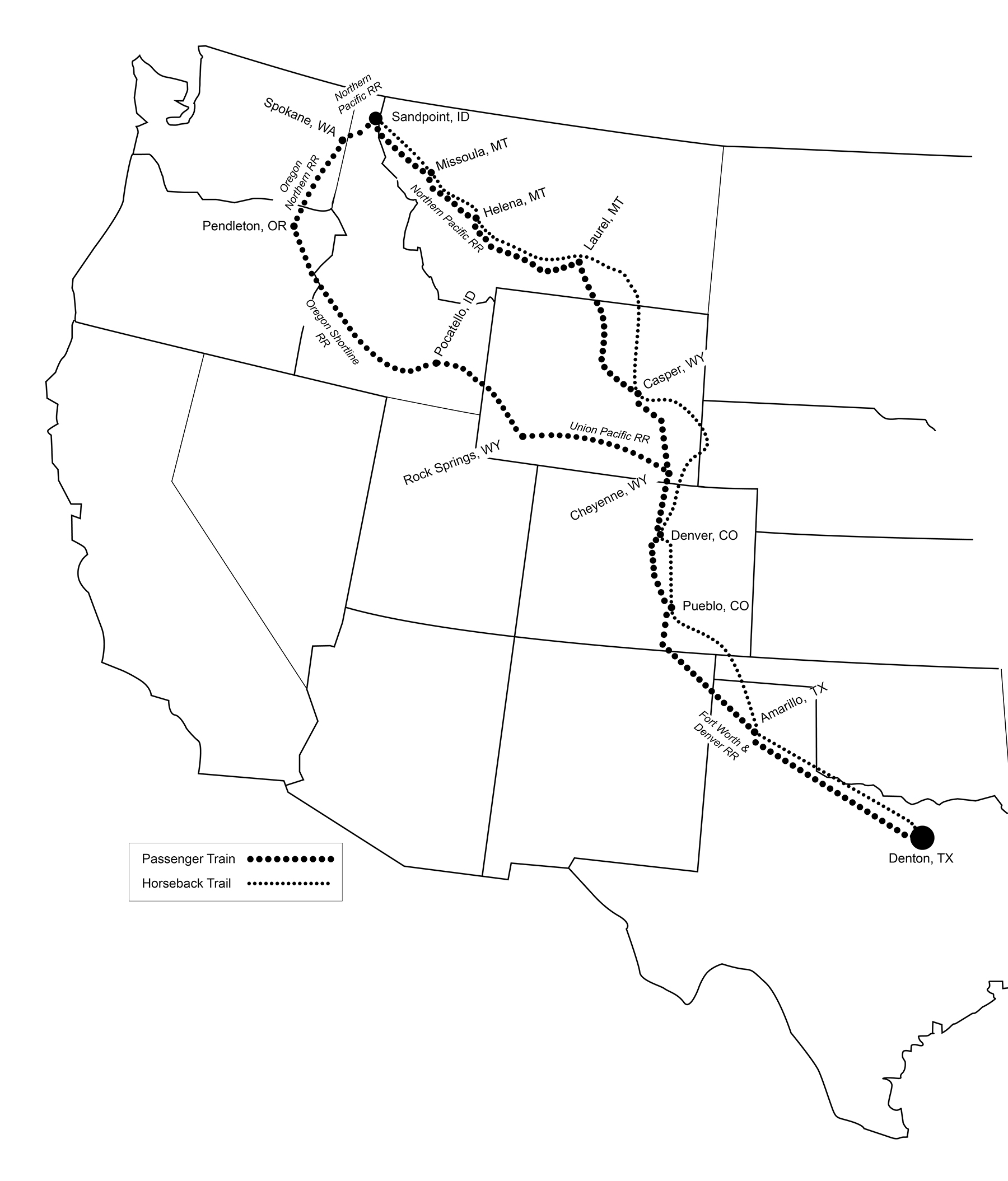

The Oregon Trail, the most popular travel route to the Northwest from the 1840s through the 1870s saw a steady decline in use with the development of the transcontinental railroad. By the time the Elsasser brothers journeyed from Denton, TX to Sandpoint, ID in the late 1880s, traveling by horseback instead of the then-ubiquitous rail, would have been an adventurous, if not foolhardy, endeavor. But, according to their present-day descendants, the Elsasser brothers swapped the modern conveniences of train travel for the far rougher and more dangerous horseback – traversing at least four major rivers and countless miles of rugged, mountainous terrain. This map shows their plausible routes, along with the possible and contrastingly luxurious rail routes they passed up.

For two younger sons of a prosperous Texas ranching family, the Homestead Act was not only a means to make a living, but a way to achieve independence, seek prosperity of their own, and carve new identities for themselves out of the North Idaho wilderness. John and William Elsasser were 26 and 23 in 1888 when they struck out from Denton, Texas and headed north in the name of homesteading.

The Elsasser brothers first explored this beautiful and wild swath of North Idaho on a trapping, hunting, and gold-prospecting expedition. Their unencumbered nature and entrepreneurial spirits led them to understand the area, not only as rife with adventure, but teeming with resources and financial opportunity.

Their earliest northern business endeavors included pole making – with one contract alone realizing “eighteen hundred dollars’ profit” (or about $50,000 today) as described in the 1903 book Illustrated History of North Idaho.

Taking their newfound fortunes back to Texas, the brothers intended to settle near their family. But, the allure of Idaho, their familiarity with its resources, and all of its untapped potential, made the move north too enticing to pass up. They were eager to invest.

Homestead Act Eligibility Requirements

Head of the Family – A head of household, a young man of legal age, or an independent widow could apply.

Citizen of the United States – A US citizen or an immigrant who had declared their intention to seek citizenship were eligible, but Native Americans were not.

Loyalty – One “who has never borne arms against the United States Government or given aid and comfort to its enemies” was eligible. *The Homestead Act, signed into law during the Civil War, precluded Confederate soldiers from benefiting from the program.

Able to Pay – An $18 filing fee or a $10 temporary holding fee (about $300 today) secured the land for the first six months.

Able to Prove – Within 5 years, homesteaders needed to demonstrate “significant improvement and cultivation” of the plot they held to secure the land indefinitely.

GOING ALL IN

John married Ollie Frances Campbell in 1891, in Texas, where their first child, May was born in 1892. Olive and May then joined John in North Idaho in their new home. Their family grew to four children with the births of James, Paul and Lora. Paul did not survive his first year. William remained unmarried, but closely connected with his brother’s expanding family.

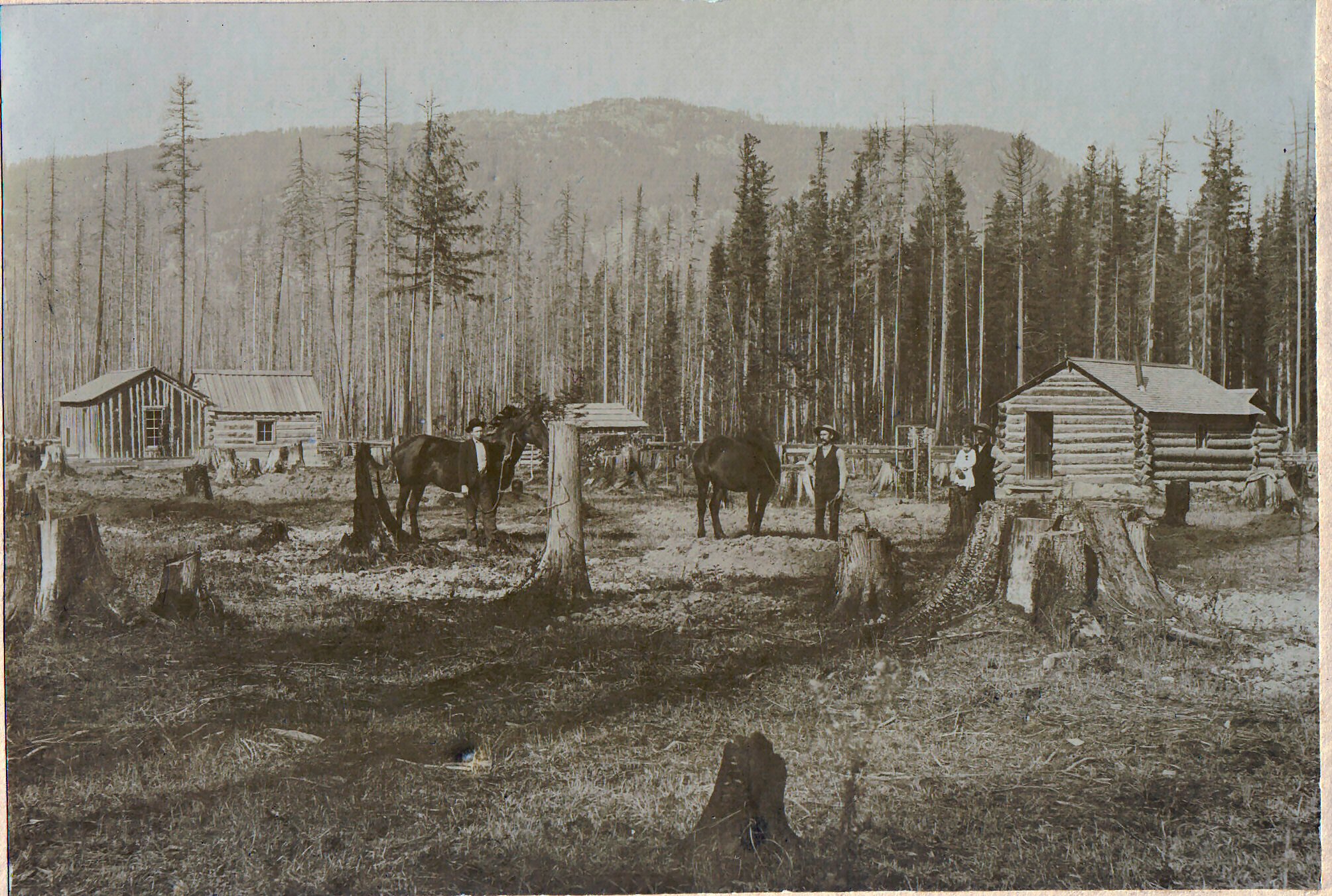

Exterior Cabins photo taken circa 1895, the year before the Elsassers “proved up” their homesteads. John (center) holds a work horse, and William (right) holds John’s baby daughter May. The five buildings on the property and the additional man in the photo, perhaps hired help, hint at the brothers’ growing prosperity. Burnt stumps litter the foreground, while acres of forest remain to be cleared. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

Ollie holds daughter May, who holds an Elsasser apple, outside a wood clad structure on the property. The family, and the crops, were beginning to flourish. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

Contending with the whims of seasonal weather and a rapidly eroding five-year deadline, the brothers had to work hard to establish their homestead. The first major obstacle the brothers faced would have been the act of clearing the land itself.

Before chainsaws, old-growth cedar was cut down with hand axes or crosscut saws. Stumps were pulled out or ground down by teams of horses, were burned, or were even blown up with dynamite. The Elsassers likely tried all three methods.

Over the five years before they “proved up” their claim, John and William lived in small log cabins on their newly cleared land. Though primitive compared to the homes they would later build, these cabins provided the essentials for survival in rural North Idaho: warmth and safety from the elements, animals, and any other settlers trying to challenge their claim.

With every small plot of land they cleared, they tilled the soil and planted their crop of choice: apple trees. Though they may not have reaped a harvest in the five years of their improvement period, the cultivation of apples would pay off in a big way down the road.

Standing next a tree stump, John with daughter May and son James (on stump), circa 1898. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

This overhead photo was taken from the mountains west of Sandpoint, possibly near the site of the Elsassers’ mine. It depicts the plots cleared by the brothers, still surrounded by thick forest in 1908. You can see large log booms on Lake Pend Oreille, near the Humbird Lumber Mill. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

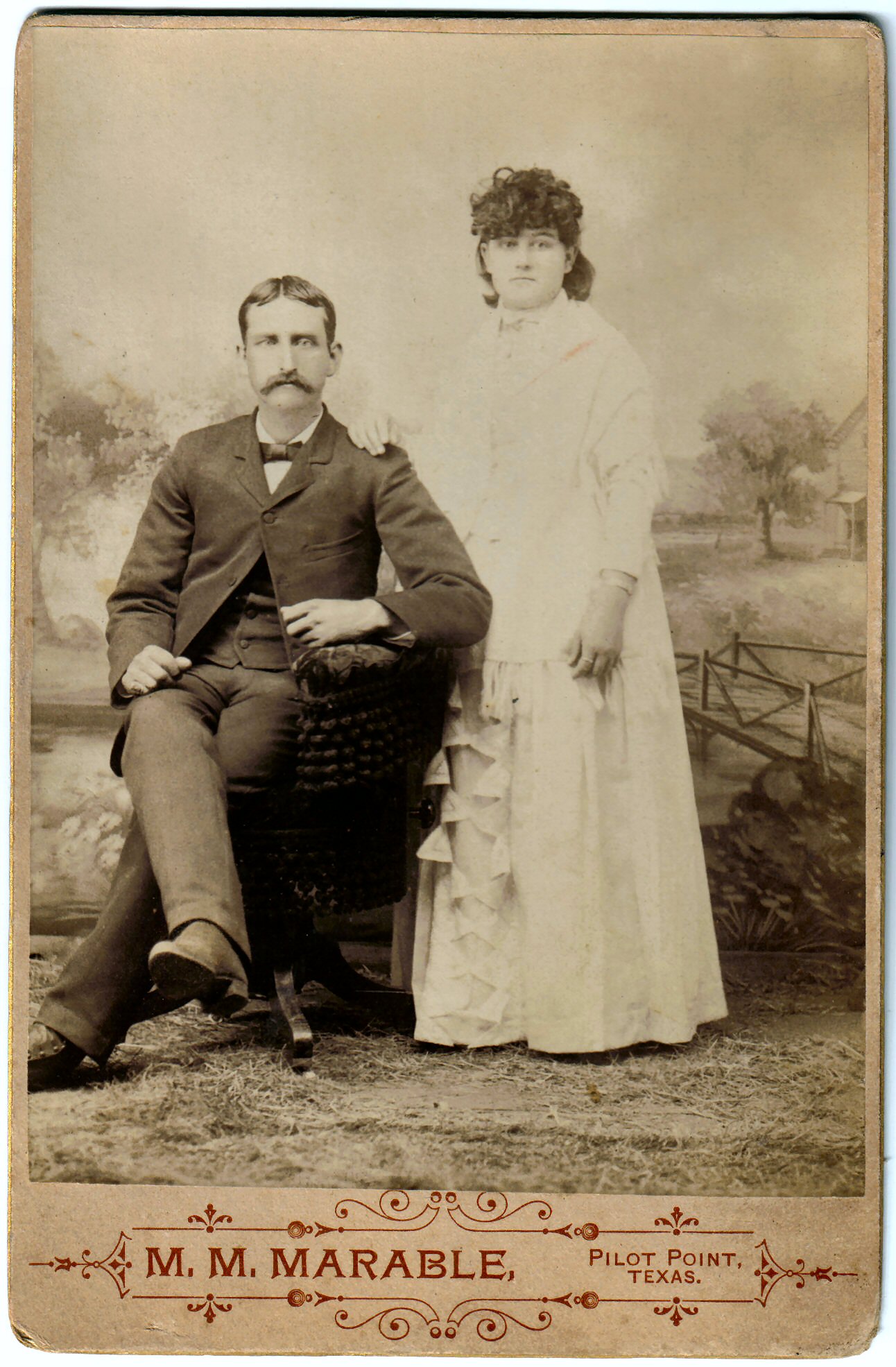

Wedding portrait of John Thomas Elsasser and Olive Frances “Ollie” Campbell. They married in Denton, Texas on April 9, 1891, when he was 28 and she was 18, then traveled together to Sandpoint. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Donna Lee Riffle Dicksson.

“John’s cabin,” believed to be the first building on the site, was likely built in 1889 on their first trip to North Idaho. As this was before they staked their claim on the land, their ownership was dubious at best and may have been contested. When they traveled back to Texas in 1891, the cabin mysteriously burned down with all of their tools inside, but undeterred, they rebuilt it when they returned. This photo shows the rebuilt cabin in 1894. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

THE GAMBLE PAYS OFF

With the requirements of the Homestead Act met, John and William could truly begin to pursue their dreams. They built identical, permanent frame houses to replace their rustic cabins, and they began to plant the seeds that would grow into their small empire.

A new century brought opportunity and good fortune to the brothers, but also grief. John and Ollie’s third child, Paul, was born in 1901 but did not survive his first year. They were likely grateful for the distraction provided by the family’s many business pursuits. By 1903, their Echo Lode mine reached $100,000 in capital stock, and they were well on their way to becoming the largest apple exporter in the Idaho panhandle. Then in October of 1903, John and William’s mother, a brother, and a sister were swept away by typhoid fever, and on December 9th, John’s Ollie died of Bright’s disease.

John remarried quickly, but it seems to have been a practical match; they divorced after the children were grown. As always, John and William threw their full efforts into work. As Sandpoint grew, they became prominent members of the community and gave their time generously to civic efforts. Other homesteaders, like the Farmins and Weils, began subdividing their 160-acre parcels for the development of Sandpoint. The Elsassers likewise started selling lots from their claims, adding to their substantial investment portfolios.

William’s neighbors probably thought of him as a “confirmed bachelor,” so he likely surprised them all when he married a Spokane widow, Mary (Wolff) Loving, in 1919, at the age of 54.

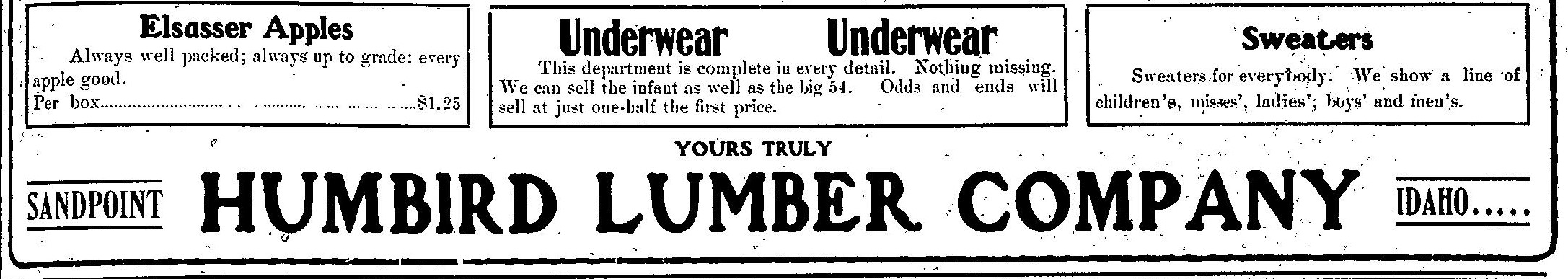

The Elsassers soon became “expert orchardists” promoting the area for growing apples and pears for profit. They would eventually have 14 acres in orchard, producing 1000 boxes of “perfect” apples yearly – roughly 6 – 8 boxes per tree – helping supply the Humbird Mercantile and shipping train carloads of fruit back east.

The Elsasser Brothers were the primary stakeholders in their backyard mining operation, the Echo Lode Mine, and investors in a regional operation, the Silver Mountain Mine – benefiting from both claims’ rich sources of iridium, osmium, and platinum (used in the creation of fountain pens).

The brothers were foundational members in the Bonner County community. They served on the fair board, as directors in mining exploration and investment, on the board of the first streetcar company in Sandpoint, and as volunteer firemen. Their apples won awards in local and regional fairs – garnering accolades across the region for their agricultural prowess.

In an indication of the prosperity and success of their endeavors, the Elsasser family and their neighbors enjoyed the luxury of leisure, holding afternoon picnics, and fostering the kind of community built on shared moments of free time.

By the early 1900s, John and William were prominent businessmen with investments in the tens of thousands. They traveled as far as Portland to serve on boards that furthered their business interests. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Dixie Plata.

A BOOMING TOWN, A CHANGING PLOT

SANDPOINT, 1900

Although the Elsassers were agents in their own development, they were also benefactors of the greater scale of local development happening in tandem with their own. When John and William arrived in Bonner County, it wasn’t exactly untamed wilderness. The Northern Pacific Railroad completed its route across and around Lake Pend Oreille in 1882, marking the beginning of the end for the steamboats and prospecting pack trails of yore.

By the early 1890s, the town of Hope was being lauded nationwide as a restive vacation destination akin to the great lakeside towns of Switzerland. Sandpoint, however, home to railroad workers, ne’er-do-wells, and prostitutes, was not gaining much good press. Upstanding Ella Mae Farmin, who homesteaded what is now downtown Sandpoint with her husband L.D., set out to change that.

By selling and donating small parcels of their claim, Ella Mae could create the village she envisioned: one with churches and schools and dignified men and women with meaningful employment. Starting with just a small handful of buildings, she used her formidable will to slowly shape the town that would become Sandpoint. Sand Creek formed a serviceable barrier from the “restricted district,” the east side of town that Ella Mae couldn’t control, where debauchery still reigned.

The largest building on the west side of Sandpoint in 1894 was the Knights of Pythias “castle” shown on the right hand side of the center photo. Knights of Pythias is a fraternal organization founded in 1964, dedicated to friendship, charity, and benevolence. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Judy Farmin.

Ella Mae Farmin first began donating parcels of her family’s homestead lot because she believed a town with 23 saloons ought to have at least one church and a school. The Methodist Church, shown here (image 1) in 1898, was originally built as the town’s first one-room schoolhouse. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Lucille Brisboy.

The Central (Defenbach) School (right) was the primary school in Sandpoint until the much larger Farmin School was built in 1908. When this photo was taken, circa 1900, John’s children May and James would not quite have started grade school here. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

Fires were commonplace among Sandpoint’s early stick frame businesses. Fires plagued the streets on the east side of Sand Creek, as in this 1900 photo (left) taken by John Elsasser, but First Avenue on the west side of the creek was no stranger to fire either. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by L.E. Bristow.

The original Farmin house at the corner of First Avenue and Cedar Street (center) was a simple, gable-roofed affair, but quite fine for its time. At the turn of the century, it was one of a small handful of buildings on the west side of Sand Creek. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Judy Farmin.

In the late 1800s, the Northern Pacific depot building was on the east side of the tracks. The wooden building had deep eaves so passengers could wait in the shade. In 1905, the depot was moved to the west side of the tracks and was later rebuilt with brick. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Carol Jones.

SANDPOINT, 1910

By the early 1910s, Sandpoint was hardly recognizable as the tiny hamlet from a decade before. Never a true “boom town,” Sandpoint’s leaders and wealthier citizens seem to have striven to keep up appearances, opting for fancier building styles akin to the much larger, more cosmopolitan cities they’d see on their travels.

As the timber industry flourished and brickyards were established, the surplus of readily available building supplies enabled Sandpoint to invest in more ostentatious and permanent public buildings that could resist the frequent structure fires that still roared through its main streets. Some of these buildings still stand today, like the old city hall, and they give us a glimpse of the evolving identity of our small town.

The Farmin School dwarfed the surrounding buildings when it opened in 1908. The imposing structure, with a gymnasium on the fourth floor, replaced the one-room schools of the early days, and illustrates the grand vision Sandpoint’s founders had for the future of their town. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Mel Nesbitt.

L.D. and Ella Mae Farmin’s original homestead eventually became the heart of Sandpoint’s commercial district, and the family built a two-story, Tudor-style house a couple of blocks north on 2nd Avenue. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donated to the collection by Judy Farmin.

City Hall under construction 1910-1911, was spacious enough to house the City offices, jail, fire department, and library. You can see a horse-drawn fire engine posted outside the nearly-completed building. Postcard courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

The Rink Opera House was a telling symbol of a small town juggling humble beginnings with big ambitions. Despite its glitzy facade, the building more often hosted roller skating and baseball games than opera performances. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

THE HOUSE THAT HOUSED COMMUNITY

Like many historic homes, there was more than one family that contributed to the Elsasser House’s legacy. Changing hands from John’s estate to another couple that would become synonymous with “community,” the house’s history continued to be written through Ardis and Wallace “Fats” Racicot. As early settlers to Bonner County, with both Ardis and Fats moving to the area in the early 1900s, they eventually settled down onto the former Elsasser property in 1940.

While Ardis and Fats didn’t have any children of their own, they helped raise local children by teaching them horsemanship. They built stables and a riding arena on what was once John Elsasser’s property. Fats had an internationally acclaimed and pedigreed Appaloosa sire, “Toby I,” who is buried on the property still today. When Ardis and Fats weren’t providing farrier or veterinary services, or starting the Sandpoint Saddle Club, they worked several jobs in Bonner County. Fats was known as one of the “best horse show announcers in the northwest.”

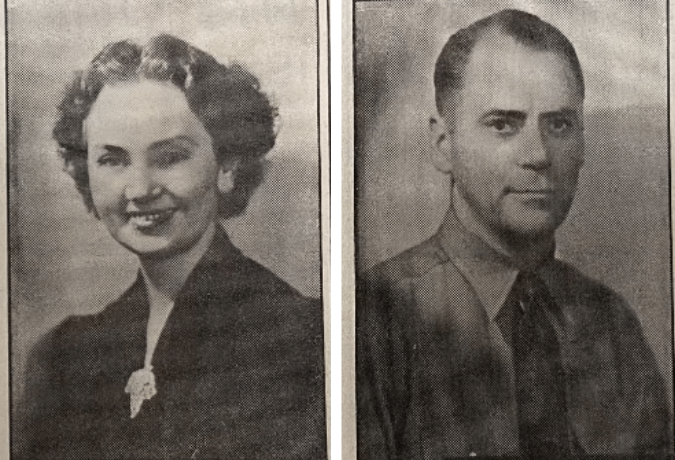

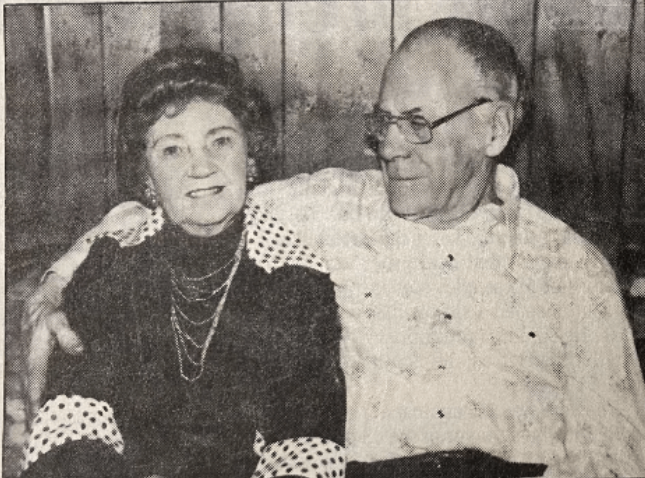

Photos from the Bonner County Daily Bee show Ardis and Fats at the time of their wedding on Christmas Eve 1923 and in 1988 on the occasion of their 65th wedding anniversary.

Ardis had a chauffeur license and drove the School Superintendent all over Bonner County in a 1930’s Cadillac. This car was outfitted with lanterns, flower pots, and isinglass curtains. Ardis was described as “fancy” whether she was riding a horse or driving a car.

Fats worked at the Humbird Mill, an early Sandpoint institution. He enlisted in the Navy during WW2 and was stationed at Farragut. He became superintendent for the Public Works Department in Sandpoint, and had his own dark room for developing his photography.

A broken hip at 98 brought Ardis’ horseback riding career to an end. She lived two more years to the age of 100. Fats died in 1989, after being kicked by a horse when he was 86. The property was sold in 1992, ending the rich history of the Racicots’ on the original homesteaded Elsasser property.

Ardis Racicot, circa 1960s, wearing a handmade costume for a Sandpoint Saddle Club horse show at the old Fairgrounds at Lakeview Park. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

BULLDOZED

After standing for over a century, the home that was erected by John Elsasser and his family, and which housed the Racicots and their community equestrian endeavors, exchanged multiple hands and quietly fell into disrepair.

Eventually, the house and its surrounding acreage was purchased by a developer, and in the fall of 2021, was bulldozed to make way for 20 subdivided single family home lots ending in a cul-de-sac – the construction of which is currently underway. The plan met the minimum zoning requirements and was approved by the Sandpoint Zoning and Planning Commission and then the City Council in September of 2022. Across the street, 3 bedroom single family homes are currently listed for $766,900.

Before the final walls were torn down, but after the first phase of demolition, our team was invited to take stock of what remained of the old building and the structures still peppering the former homestead. A narrow staircase climbed toward vaulted ceilings, and layers of wallpaper revealed themselves in beautiful swaths of time-period patterns. Craftsmanship was on display in the simple, elegant details of the trim around a bay window and in the hand-forged square nails scattered on the floor. History saturated the milled boards that made up the walls’ sheathing and settled like dust into the layout of the living room. It was easy to imagine chairs pulled together for a conversation or up to the bay window to gaze out over flower boxes and mature willow trees toward William’s property.

Through taking real estate quality photos, we hoped to capture the feeling of beauty and untapped potential of the old house; with all the opportunity, history, and legacy it once held escaping through the cracks now permeating its storied walls.

WHY AND HOW THIS HAPPENS

Our town changes over time guided by influences at the largest scales (i.e city plans, neighborhood subdivisions, and government jurisdictions) and the smallest scales (i.e placement of a crosswalk, storefront awning designs, and homeowner renovations). Visions for a future are imagined by everyone from the Idaho Transportation Department and City-employed urban planners, to a resident dreaming of a one-day addition onto their old home.

The City of Sandpoint’s comprehensive plan introduces our vision for community design, trajectory, and growth, using broad brush guidelines to shape choices at all of its varied scales. Tools like zoning and building codes are adopted to more specifically influence the shape, size, and scale of our built environment, including considerations for safety, accessibility, requirements for light and air, waste management, and utility infrastructure.

Codes are the bare-minimum requirements people have to meet to execute a project, whereas the comprehensive plan is meant to act as the inspiration for a project’s contribution to the collective identity of our town. The code might require your home to be set back five feet from your neighbors’ property, but not dictate whether it should be finished with vinyl siding or board and batten cedar planks.

When pursuing a new project, developers must consider the minutiae of the code – without necessarily being beholden to the grand vision of the comprehensive plan. Code compliance and comprehensive plan considerations are among many complicated steps and financial risks they face at the onset of a new development. Economic volatility further puts these groups’ and individuals’ assets at risk, but like prospectors, they assume these risks while also seeking economic gain from their efforts. Often, to reduce uncertainties and increase their potential profit, they want to build in the simplest way, removing the site’s existing obstructions and scraping away prospective complications to start with a clean slate: tabula rasa.

But “clean slates” are often incongruous to the community’s collective memories and the sentiments attached to them. Our minds struggle to accept that a landscape once rich with life is now an empty lot devoid of character. Over time, though, as the land is redeveloped, our memories, and the history behind them, fade. With new houses will come new memories, but the full story of the land diminishes unless we make the effort to document it.

There are many strategies employed to remind ourselves of what once existed and weave it into our future urban fabric. Such methods include: historic preservation, adaptive reuse renovation, integration, and reuse of a building’s facade. These strategies can be incorporated to varying degrees, all of which would continue to cultivate the character of our urban environment.

Historic Restoration seeks to preserve the original character and can typically result in the most restrictive construction and post-construction uses. In most cases, this creates a “museum” out of the structure or keeps its original use.

Adaptive Reuse alters the use of a building while still maintaining its original character, typically requiring structural upgrades, and upgrades to the exterior envelope for weather. Not being beholden to the original use, there is more flexibility for building types through this method.

Historic Integration/Addition incorporates the original structure into an addition or new surrounding building, maintaining much of the original character – the old and new are merged next to one another.

Facadism keeps the exterior facing building skin only while building a new structure and envelope within it.

MickDuff’s Brewing Company

Mickey and Duffy Mahoney, Owners

Adaptive Reuse & Historic Integration

In 2020, Mickey and Duffy Mahoney, owners of MickDuff’s Brewing Company, completed the historic renovation of the old Federal Building. Built in 1927 in the Spanish Colonial Revival style, the Federal Building was home to the post office and later the library. In transforming the building into their restaurant, the Mahoney brothers restored or recreated many original historic details, like custom bathroom fixtures and mail-slot inspired mug shelves that evoke the original era.

“Preservation is really important to Sandpoint. It’s a way to communicate our understanding of the past to future generations”.

The Federal Building, which housed the post office and later the library, is shown here upon completion of construction in 1927. Photo courtesy of the Bonner County Historical Society, donor unknown.

The Federal Building after its restoration in 2020 by Mickey and Duffy Mahoney. The building is now home to MickDuff’s Brewing Company. Photo courtesy of Mickey Mahoney.

South Sandpoint Residence

Kris Contor, Architect

Historic Restoration & Renovation

Sitting empty for several years and in a bad state of disrepair, architect Kris Contor worked with his client to restore the original character of this turn-of-the-century bungalow. “It still had classic touches worth preserving,” explained Kris. The original tapered shingles columns, dormer shed roofed window and craftsman details inspired the renovation and addition, with new elements harkening to the rich tradition of bungalow designs.

“The original intent and aesthetic of a home often is marred over the years with various ‘improvements.’ Historic Preservation is a clear path forward to eliminate the disjointed ideas that accumulate over time, compromising our built environment and [the memory of our] past.”

The bungalow residence before and after renovation. Photos courtesy of Kris Contor.

Culvers Crossing Development

Nancy Hadley & Bonner Community Housing Agency

Natural Historic Preservation / Historical Referencing

This development went through the city’s Planned Unit Development process to offer a unique and thoughtful community-focused alternative to development in Sandpoint. In partnership with the Bonner Community Housing Association, the Idaho Housing & Finance Association, and a local developer, this 49-unit development on 6 acres is meant to blend in with the existing context. They are doing this by maintaining the existing second growth trees and creating a greenbelt along Boyer, creating smaller units to appeal to a lower income demographic, a mix of housing scales and types to promote economic diversity, creation of a public park adjacent to Boyer Ave, and a local housing affordability program. This program is for locals who have lived in the area for two or more years, hold a job, and are within 5% of 60-120% median income range for the area (AMI). This would mean families or individuals with a household income of $29,480 – 67,000 can apply to purchase these homes.

“I’m second generation, born and raised in Sandpoint, and I just know how difficult it is to make a living here and to stay in Sandpoint,” Hadley said. “So I was really looking for an opportunity to give back to a community that has given me so much.” Bonner Daily Bee